Crafting with Cricut Joy “calms me down,” says Army Veteran with PTSD

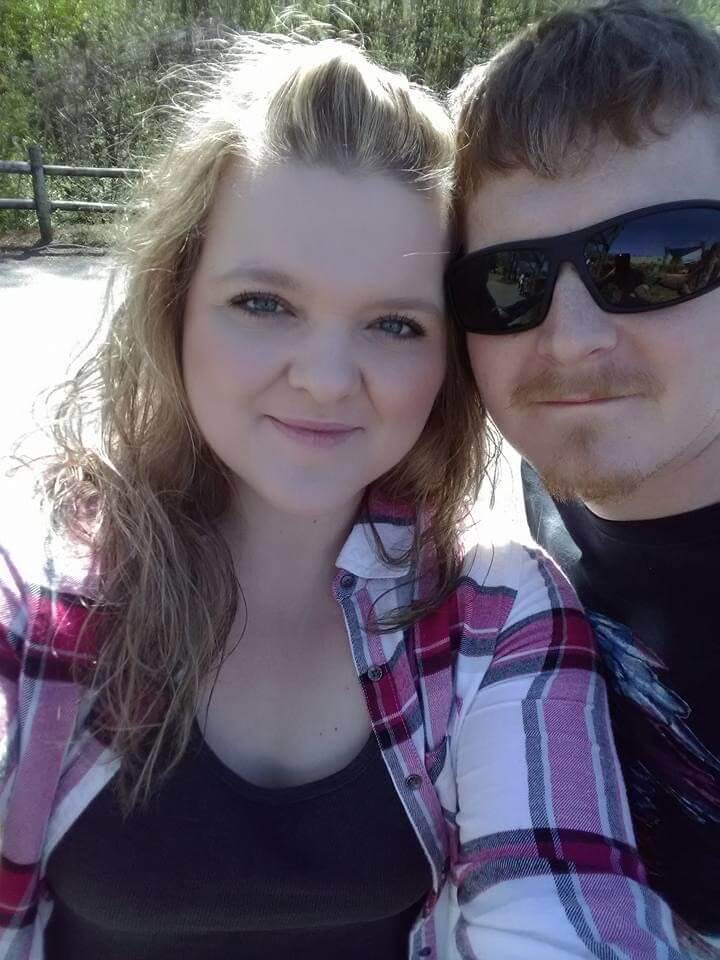

Seeing the Cricut Joy display at Michaels got Kayla Davis excited to create her own personalized Disney mugs, MagicBand stickers, and other accessories for the next family trip to Disney World. But, she willingly gave that up for her husband, James, after seeing how happy the machine made him.

In a popular Cricut Facebook Group, Cricut Craft Life, Kayla posted that “he cried actual tears” when she gave James the machine. Nothing had helped with his severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) until he discovered Joy. It “helped more than his therapist” and “better than coping techniques” he received from doctors, says Kayla.

I would recommend it to any veteran who is struggling with anxiety.

James Davis, Army Veteran

James Davis was in the Army for five years as a technical specialist. It took him over two years to learn the components of his position before getting assigned to a permanent duty station. Then, he did one tour to Iraq before the military ended his contract for medical reasons.

“My Humvee took a double car bomb and I lost a lot of my hip,” James told me in a strong Southern accent as he continued weeding a mandala just cut on his Cricut Joy. “I got really bad vertigo, balance issues… that’s the reason I shake a lot… so they didn’t let me stay in and reenlist.” Though, getting cut from the military and a bad case of vertigo wasn’t all he got.

“James is 100% disabled and goes back and forth between the VA two to three times a week,” says Kayla. Understandably, he also “hates car rides.”

“I don’t like being on the interstate because, over there, they had a place called IED interstate,” James explains. “That’s where they planted roadside bombs all the time.” As James continued weeding his mandala, he opened up a little more, vulnerable but focused on his project. You could tell that talking about what happened wasn’t easy for him. But, he wanted to provide a little context for what his anxiety was like “after that double car bomb.”

James described driving in the fast lane as “a panic.” “You’re always looking at the edge of the road wondering if there is something planted there,” he says. It’s just the “way it was over there.” James added, “It makes it harder to go places and actually do stuff with the family.”

Kayla admits “staying home is something that we’ve gotten used to because he can’t deal with big crowds.” Before COVID19, the Davis family would go to the zoo with their son, Cayden. Though, anxiety would oftentimes get the best of James and he’d return to the car. “He was always afraid someone was going to do something,” says Kayla.

The VA tried to help. “There are programs that help him work with the public,” says Kayla. “But at his last job, there were individuals that made jokes about making grenades which didn’t work well for him.”

When James met Kayla shortly after returning to Tennessee in 2009, he lived alone and mostly kept to himself. His PTSD “wasn’t as bad then,” he said. As time went on, “it went way downhill, bad.” Everyday situations – like being at work, in public places, or in any type of crowd – made it worse for him.

People think it gets better, but it really doesn’t. The more you think about it, the more you dwell on it. You wake up and don’t move because of it. It gets worse everyday.

James received medication for his condition. The doctors told him “to breathe, to do this and that.” “It doesn’t really help,” he said. “It kind of calms you down here and there, but it comes right back.”

The hardest part is trying to forget it, but you can’t. It doesn’t really matter what you do, you can’t forget it. It never goes away. I’ve tried. People don’t realize how hard that is to see, and how hard it is to forget. You don’t forget it.

The worst part about the army was being in the field. “It was seeing the stuff that people are capable of doing, seeing the stuff they do, and do to other people,” says James. Everything changes because “when you’re deployed, you don’t do your job.”

When you’re deployed, you kick in doors, run people down, and do all of that stuff.

When James was stateside during his service, he worked on “everything electronic” in the military. “I like doing things with my hands,” he says. “It calms me down and keeps me steady.”

Aside from growing up in a family that remodeled homes, James’ grandfather did a lot of woodworking and his grandmother made quilts and table centerpieces that she sold at the flea market. “If I wasn’t building cedar chests and rocking chairs, I was in the basement helping do quilts, quilt squares, and centerpieces,” he says. He even admits to “doing flower arrangements at 8-years-old.”

To combat his PTSD, James says “the therapist just tells me to count to ten and breathe.” It doesn’t help.

They tell me to go to the corner, to be by yourself. I don’t want to be by myself. If I’m by myself, I want to be doing something. I’m antsy.

Little did the Davis family expect that James would find a little solace with his wife’s compact cutting machine. “This zones me into one thing and I’m not thinking about a bunch of stuff,” he says. “It calms me down.” One night, he “sat humped over” watching the machine cut without realizing his feet had gone numb. Weeding and cutting with the Cricut Joy has given James a new favorite hobby. “This beats it all,” he even said.

It’s “already helped a little bit long-term.” James described how he would see beyond the crowds that normally gave him anxiety to find projects all around him. “Oh, I could cut something for that,” he’d say to Kayla while at the store. “Let’s go to the Joy section,” Kayla said finishing his sentence.

I called James a “weeding machine,” and he smiled at that remark. It seemed like he found that endearing, in fact. Kayla proudly told me he had been cutting army and navy crests to hand out to veterans for “when the VA opens back up.”

The effect that Cricut Joy has had on James is undeniable to Kayla. “He’s calmed down a lot,” and it’s also given him a lot more patience. “He would get agitated over nothing,” she says, “but ever since he’s been doing this, he takes a step back.”

James acknowledges that his PTSD has also affected Kayla. “I know I get on her nerves a lot, aggravate her a lot, and stress her out.” He doesn’t deny that he gets “stressed out really easy” or gets “angry easily because of” his PTSD.

For [the Cricut Joy] to actually calm me down is refreshing because I know I’m not getting on [Kayla’s] nerves. I have pretty bad nightmares so it’s nice not to think of things that happened over there for a change. It’s helped us both.

Together, the two have bonded over Cricut and crafting. Kayla often creates designs for James to cut. And, James often makes projects for Kayla to decorate. Although, “I still haven’t gotten to touch [the Cricut Joy],” says Kayla.

Cricut is honored to highlight this community story for Mental Health Awareness Month and would like to thank Kayla and James Davis for sharing the details about how crafting has helped them heal. We especially appreciate their bravery for providing us with their candor and trust. Thank you from the bottom of our hearts.